As part of the World Mental Health Day webinar on 10th October, we sent out a survey to the webinar attendees.

While we only have a small sample of 28 responses to the survey, we believe that there are still some useful learning opportunities that firms can take from it. Two IP founder, Dr Anna Molony, shares her thoughts on these.

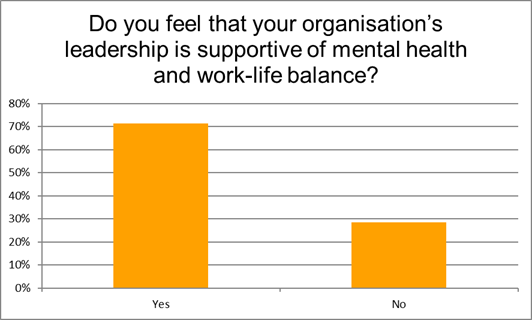

Q1: Do you feel that your organisation’s leadership is supportive of mental health and work-life balance?

The answer is 70% ‘Yes’, which appears positive. However, the comments highlight some potentially worrying issues. While most respondents are positive about having flexible working, the comments suggest that this doesn’t always translate into work-life balance. And while many are positive about the mental health training and support that their firms provide, the comments suggest that some firms still have a poor understanding of how to support mental health issues.

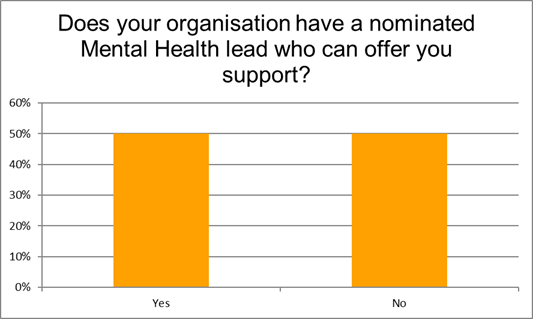

Q2: Does your organisation have a nominated Mental Health lead who can offer you support?

An interesting 50:50 yes:no split, suggesting that some firms could be doing more to provide mental health support.

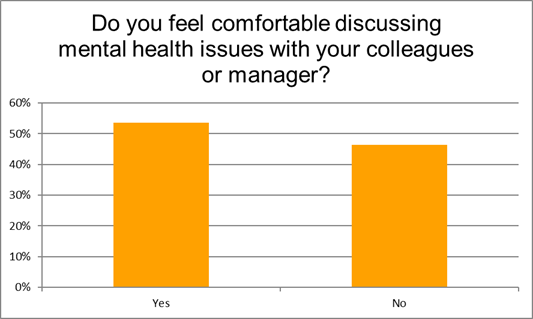

Q3: Do you feel comfortable discussing mental health issues with your colleagues or manager?

A similar split as for Q2, which one could interpret as indicating that a lack of mental health lead is making it more difficult for people to discuss their mental health. The negative comments also highlight a potential problem that people believe that raising mental health issues with a colleague/manager will be seen as a weakness.

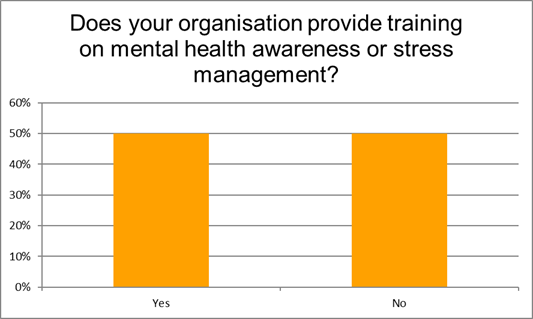

Q4: Does your organisation provide training on mental health awareness or stress management?

While half of respondents answered ‘Yes’ some of the comments suggest that the mental health training that is being provided at some firms is not very helpful.

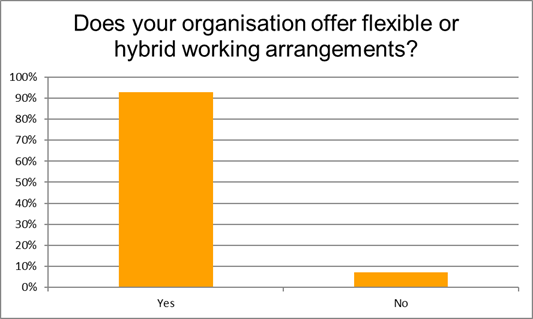

Q5: Does your organisation offer flexible or hybrid working arrangements?

An overwhelming number of respondents report that their firms offer flexible or hybrid working arrangements. The comments indicate that some firms are entirely flexible, while others require a certain number of days in the office each week, which appears typically to be 1-2 days.

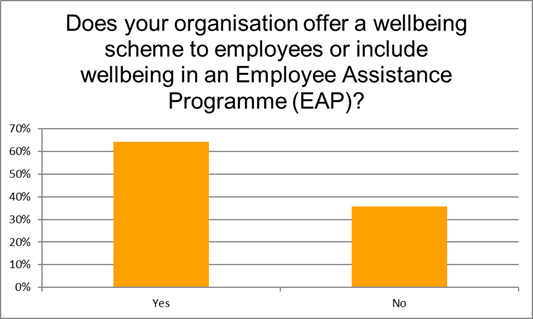

Q6: Does your organisation offer a wellbeing scheme to employees or include wellbeing in an Employee Assistance Programme (EAP)?

65% of firms offer a wellbeing scheme or include wellbeing in their EAP, but nearly every comment reported that the respondent had not used it.

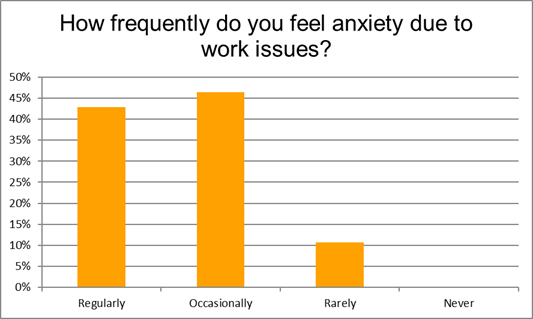

Q7: How frequently do you feel anxiety due to work issues?

With over 40% of respondents reporting regularly feeling anxiety due to work issues and only 10% rarely feeling so, we’d suggest that this might be something that firms need to investigate to find out what could be causing work-related anxiety.

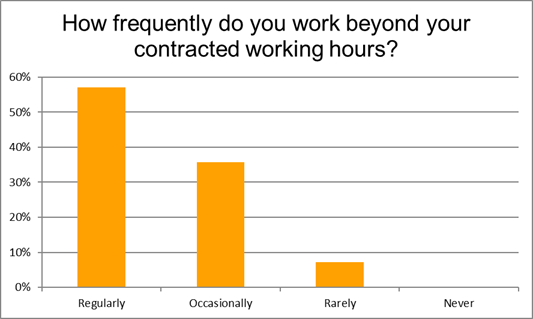

Q8: How frequently do you work beyond your contracted working hours?

Read together with the answers to Q1 and Q5, it would appear that flexible working may not be helping everyone to manage their work-load within their contracted hours. With over 57% of respondents regularly working longer than their contracted hours, do firms need to reconsider whether the work-loads that they are expecting people to manage are realistic?

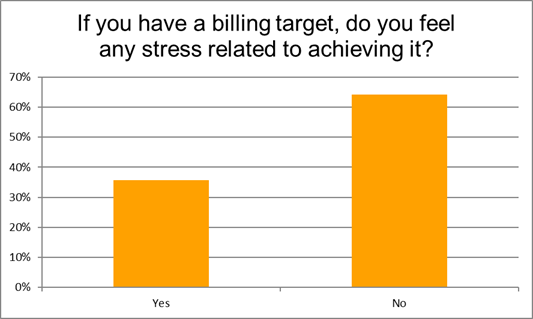

Q9: If you have a billing target, do you feel any stress related to achieving it?

While over 64% of respondents reported that they don’t feel any stress related to achieving their billing targets, is that because they are working longer hours in order to do so? The answers to Q8 suggest that it might be.

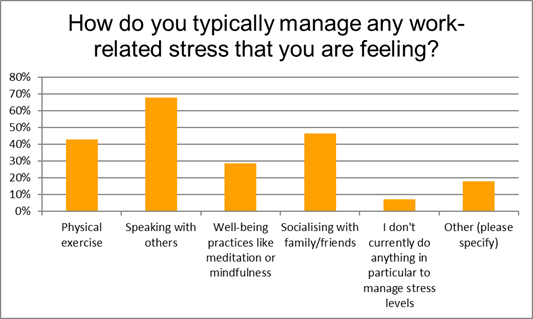

Q10: How do you typically manage any work-related stress that you are feeling?

It is encouraging to see that so many people are finding positive ways to manage any stress that they are feeling.

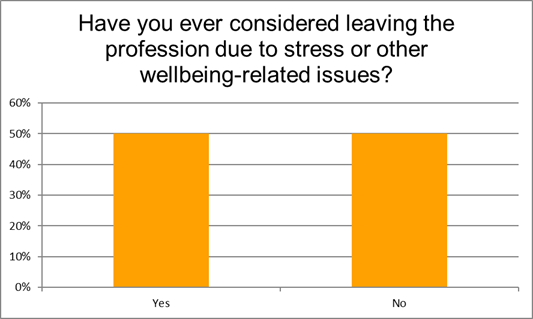

Q11: Have you ever considered leaving the profession due to stress or other wellbeing-related issues?

Half of respondents have considered leaving the profession. The comments identify work-load, pressure of meeting deadlines, worry about missing a deadline and poor management as reasons for doing so.

Summary

There have been some significant positive changes in the IP profession in recent years with the introduction of flexible and hybrid working, and improved awareness and support for mental well-being within the profession. However, it feels like very little has changed in the nearly 30 years since I joined the profession in terms of high work-loads and the stress and anxiety that these, and the fear of missing deadlines or making a mistake, can cause. I believe there is still much room for improvement if we truly want to make the working lives of patent and trade mark attorneys, IP solicitors, paralegals and support staff better.