Often when talking to investment professionals one hears mention of “strong IP” as a desirable feature in target companies. It is not unusual to learn that the IP policy of an investment vehicle is only to invest in companies with “robust” IP, or some such.

What do these companies mean when they refer to “strong”, “robust” or “high-quality” IP? Do they really know what separates “strong” IP from weak IP? Is it truly possible to talk of “strong IP” in a start-up, whose patent applications have not progressed to the stage of allowance (let alone being tested for validity in a court or opposition action)?

This article seeks to clear some of the fog surrounding the so-called strength of intellectual property assets, and especially patents. By the end you should have a better idea of the main factors; and I can provide further information in a tailored seminar or webinar for those who want to know more.

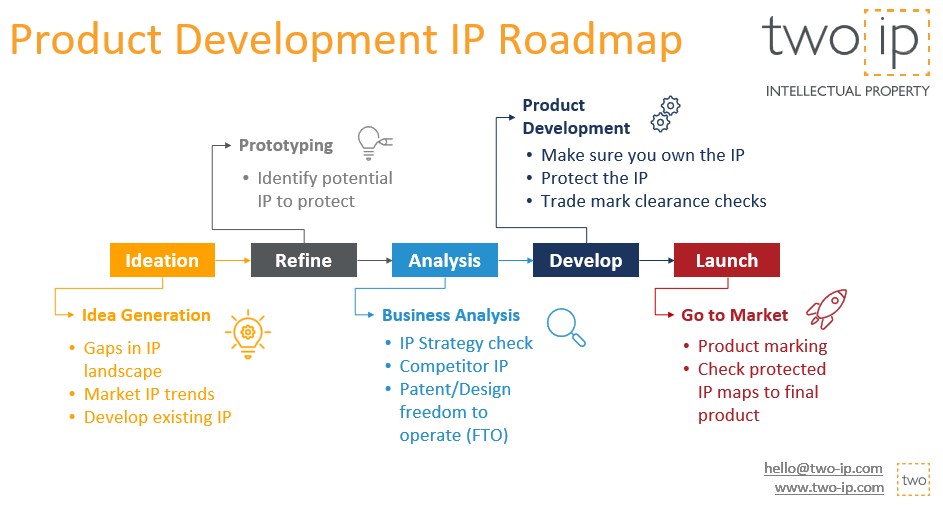

Unavoidably we start with a little information about the process of obtaining a patent, since the stage reached on a patenting journey can provide useful pointers.

Before it All Starts: Pre-Filing Patent Searches

It is readily possible to undertake investigations, usually referred to as “searches”, before filing of a patent application. The aim of these is to try and establish whether a new invention is novel, before the cost of preparing and filing a patent application is incurred.

In an ideal world every company, large and small, would have access to efficient patents searching services; they would find out about the novelty of each invention at an early stage; and they would save much wasted effort and cost spent pursuing patent applications for non-inventive ideas.

Actually in many ways this ideal world exists, because reputable and professional searching companies are out there ready and waiting for searching and reporting instructions. They have for many years been improving the accuracy of their searching techniques and the useability of their reports, and their services are available to anyone who chooses to pay for them.

So our first pointer is that any potential investment target that can point to effective pre-filing searches producing favourable indications of invention novelty (and, better still, education of its inventors and technology managers on the meaning of the search results) probably enjoys a greater likelihood, than a company without this information, of the company’s patents being “strong”.

Money Talks

Why then do not all start-ups commission pre-filing searches? There can be several explanations, including for instance a conviction that there is no-one else researching the exact technology space of the company in question (such that searches would be a waste of time). This however is a relatively rare reason compared with the admittedly prosaic, but more common, one that start-ups very often simply have not budgeted for pre-filing patent searches or their interpretation. A far-sighted investment target therefore is one whose seed funding includes an allowance for searches and, as explained below, a patenting strategy based on the results of those investigations.

Note the emphasis on this being desirable at the seed funding stage. Any invention forming the subject of a patent application must be novel as of the application filing date. This means that pre-filing search results are likely only to be of value if they are generated, and any desired patent applications filed, before any non-confidential disclosure of the invention occurs. Unless a start-up has a well-developed confidentiality policy that is effectively enforced there is a real chance that a product launch will have occurred or a non-confidential disclosure made at an early stage in the company’s life cycle. In order to guard against the risk of rendering the invention unpatentable on lack of novelty grounds it is strongly desirable that searches are completed at an early stage and, depending on the search results, at least an initial patent application filed during the same phase.

So another useful pointer is that the seed funding of a start-up includes a budgeted amount for intellectual property searches and applications. In brief, in many cases it is too great a risk to leave these aspects until a later stage of the company’s development.

Strategic Interpretation

Merely instructing the completion of pre-filing searches, however, while a sign that a company takes IP issues seriously does not mean that the search resultsare good (or bad, or indifferent). In other words it is necessary not only to commission searches; but to interpret their results as well. Another pointer therefore to a company having justified confidence in the strength of its IP is the existence of an analysis, by an experienced professional, of the results of pre-filing searches.

Better still is an action plan based on the analysis. This may involve changing the emphasis of the company’s patent applications, alterations in the lists of countries where protection is desired, the undertaking of additional R & D to counteract third party patents revealed by the searches, or any of a range of further options. Regardless of the exact form it takes the existence of a search-derived plan is a very good indicator that the company’s IP is in good shape (or is in the process of being improved, at any rate).

Filing Milestones

The process of obtaining a patent is lengthy and involves a number of stages. The filing step is the first one and on its own often tells little about the quality of a company’s IP, being in one sense no more than a statement by the applicant entity of what it thinks it ought to be able to protect. Investors should not be misled about patent quality by the mere filing of a patent application, no matter how bold the claims made in it.

A more important, subsequent stage is the issuing of a search report by a reputable patent office. This should be consistent with the results of any pre-filing searches (which do not carry official weight but as explained can be powerful indicators of patentability and related aspects).

However sometimes the official searches throw up unwelcome surprises. A target company that has encountered trouble at this stage should be candid about unexpectedly adverse official search results; and should show itself to have a flexible IP strategy at such a time.

In contrast a company that is not open about adverse developments at this stage either may lack confidence concerning its IP; or may have realised, too late, that its initial patent application(s) did not contain sufficient descriptions of useful variants on the basic invention as to support amendments addressing the effects of unexpected, unfavourable prior art. Neither situation is a good indicator in a target company. Indeed a failure to recognise potential grounds of IP invalidity can have far-reaching effects and may significantly devalue the IP assets of a company.

Country Strategy

Another key point concerns the range of countries in which a company files patent applications. Ideally a company will include budgets for patents in key jurisdictions. What counts as a key jurisdiction may be judged with reference for instance to the presence of manufacturing rivals, potential sales markets and the ease (or otherwise) with which patents and other IP rights can be enforced. Look for signs that seed and A-Series funding include allowances for a patenting programme that matches the “key jurisdiction” strategic analysis.

It’s a Numbers Game (or Is It?)

The subject of country strategies leads nicely on to a caveat, which is not to be unduly impressed by the sheer numbers of patents (or patent applications) a company possesses. There is no limit to the number of patent applications a company can commission but this on its own says nothing about the quality of the underlying inventions or indeed the skill with which the patent applications have been drafted. A more detailed investigation is required, and simple numbers of patent applications on their own may be a misleading indicator.

This is especially true when multiple patent applications relate to say only one or two patent families (i.e. groups of related patents/applications usually directed to only one underlying invention). A single patent family can be extended to multiple countries and thereby give rise to tens of patent applications. This allows a company truthfully to say it has 10, 15 or however many patent applications, without admitting that it has only one invention worthy of the name. It is important to be alert to careless terminology when talking about the numbers of patents owned by a company.

Evergreening

“Evergreening” in the context of IP refers to the practice of having a continuing R & D schedule that gives rise to developments based on the originating technology of the target company. Evergreening is often extremely useful in prolonging the overall patented life of a product and moving the market in ways that confound rivals. This can be so even if an initial patent application is regarded as “pioneering” and hence of particular value.

As is always the case, the more IP a company requires the more it costs; but a thought-through approach to evergreening suggests a sophisticated attitude that is not always encountered. It is another sign of the strength of IP in a company.

Other Forms of IP

This article focuses chiefly on patents, but these of course are not the only IP rights available. Companies that use (for example) registered designs to protect particular product aesthetics or packaging; trade marks to protect brands; and recognition of unregistered IP rights again show themselves to have a deeper understanding of intellectual property issues than others.

A particularly good indicator in my view is the existence of an effective trade secret recording and management process. This often goes hand in glove with well-organised R & D practices and is a sign that the target probably will find it comparatively easy to defend attacks on the validity of its IP assets. A deep dive into the non-patent IP assets in other words often reveals much about the overall attitude of the company to IP topics; and a company with high-quality IP practices should be able to produce schedules of such assets without difficulty.

Likelihoods

As indicated I can only talk in terms of the probabilitythat a company has strong patents. Why is that? Well, firstly, despite all the advances in database searching and the recent introduction of AI into the searching process, there remains a subjective element in at least the interpretation of search results if not in their initial generation. That subjective element carries through to examination of a patent application, in which a human (i.e. a patent office examiner) is responsible for determining whether a patent should be granted.

Even once a patent is granted there remains an uncertain aspect of its validity; and partly for this reason a granted patent remains open to an invalidity-based attack throughout its life. Judging of patent validity in litigation will remain the preserve of humans for the foreseeable future and this further means that unless the validity of the patents is tested in court we can never state with complete certainty that a company’s patents are “strong”.

Nonetheless the more of the foregoing features one can identify, the more input there is to a company’s strategy by experienced IP advisors and the greater the confidence with which the target company can point to the positive features, the greater is the chance that one has encountered an investment target with “strong” IP. This is all the more likely to serve the purposes of (a) acting as a barrier to entry by competitors; (b) becoming a vehicle for licensing revenue; and (c) adding to the asset value of the company.

Do you want to know more? Perhaps you still have questions?

– How do you effectively instruct patents searches?

– What do you do when adverse search results arise?

– Which patent offices have thorough examination processes?

– In which countries is patent enforcement most effective?

– Are certain countries important for particular technology areas?

– What details of a company’s IP portfolio really make a difference, and which ones are problematic?

If you would like me to provide a free, tailored webinar or in-person seminar on related aspects, please get in touch at TPowell@two-ip.com.